As a parent I don’t think there’s anything that can prepare you for your child’s diagnosis of cancer. It’s the kind of thing you see in BBC dramas and hope it doesn’t happen to you. When it happened with our two year old daugher, Emmeline, both Clare and I approached it in the same way: “Let’s fix the problem and start finding a solution first and there will be time to cry and deal with whatever emotions we have later on while the solution is being worked on”.

As a parent I don’t think there’s anything that can prepare you for your child’s diagnosis of cancer. It’s the kind of thing you see in BBC dramas and hope it doesn’t happen to you. When it happened with our two year old daugher, Emmeline, both Clare and I approached it in the same way: “Let’s fix the problem and start finding a solution first and there will be time to cry and deal with whatever emotions we have later on while the solution is being worked on”.

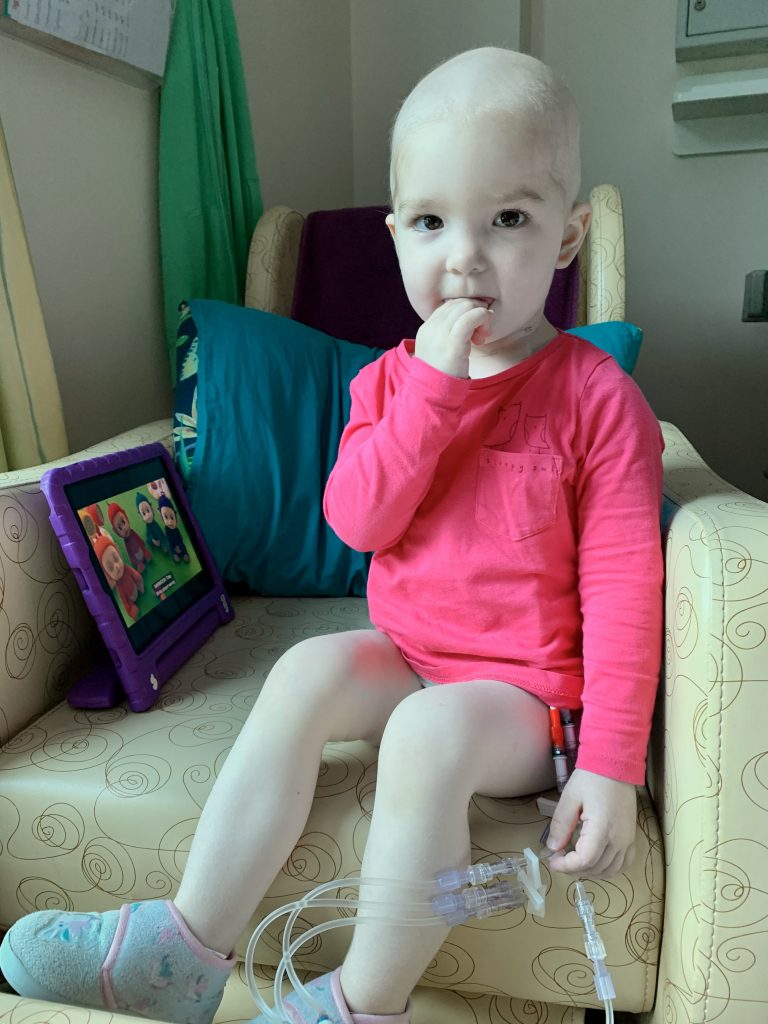

Following diagnosis, we were offered 24 hours to process the news or to put Emmeline immediately into theatre the next day to fit a portacath to enable treatment to start. With incredulous faces we wondered why we were being offered 24 hours to waste when we could be doing something; we chose the surgery. However, after Emmeline had gone under anaesthetic and was taken through the mystical theatre doors, the emotions came out. Several anaesthetics and operations later and it’s never easy to kiss her and send her off beyond those theatre doors. It’s not ‘Stars In Their Eyes’, that’s for sure. Clare and I take it in turns now to take her through as only one of us can go into the room. Every time I’ve done it, when Emmeline has fallen asleep the anaesthetist has said ‘give her a kiss and tell her you love her’ and every time I’ve done just that. And every time, I’ve completely broken down in the corridor outside the room crying on the shoulder of whichever nurse has had the bad luck to be chosen to guide me back out to the main waiting area.

Emmeline’s first surgery in January 2021 sticks out for all of those emotional reasons. Following some hard months of chemo (including Christmas Eve and New Years visits to the hospital) and our son, Edward’s birth in November 2020, I was in quite a dark place and was somehow convinced that she wasn’t going to come back. I remember sitting in the ward room the night before surgery while she was having a transfusion ready to go to theatre early the next day and I was looking at her clothes, her coat and her books and toys and thinking that she would never wear them again or play with the toys or read. That I’d never teach her anything. At that point, she was happy and hadn’t had treatment for a while. She’d been playing with the nurses in the corridor which was lovely to see but somehow it made everything even more difficult. It’s harder to imagine her happy and possibly dying the next day than to go from being ill to dying somehow. Thankfully she survived and the relief of emotion the next day around 2 pm when I was told that she was ok was massive. If not for Covid, then everyone in the room would have been hugged for giving me the news. I can remember phoning Clare straight away (Covid restrictions meant only one parent could physically be there) and crying so much that I only managed to get the important ‘she’s ok’ piece of news out.

Then there’s the guilt that comes from investing more time in one child than the other two. The guilt of not fully forging a relationship with your son until he’s two years old. It sounds ridiculous but when there’s so much investment in one, with the best will in the world, some things sometimes slip. Against all of this, my older daughter, Julia, finished her A-Levels with amazing results and went to university – with, what I perceive to be, an absent father.

Whatever my children say, and hopefully they will be forgiving in the future, you always feel that you should be able to do everything and juggle all the balls. You know deep down that it’s ok if you can’t and you agree with what everyone tells you: that you are doing great and they can’t imagine what you are going through and that you need to take time out for yourself. They ask ‘How do you manage to work as well as go to the hospital?’, ‘how do you look after the house, the kids, the car, each other, get dressed, get shaved, not look like a complete lunatic?’

You would say the same things to anyone if the situation was reversed and they are 100% right. You do need to take time emotionally, you do need to look after yourself and you don’t have to do everything at once or juggle all the balls. But when it’s you – all that wisdom sounds like a cat poster. When it’s you, you believe that you should be the one who is capable of doing everything at once. Of keeping all those balls in the air. Because you are different. You are the one to do it. You can do what others can’t.

You would say the same things to anyone if the situation was reversed and they are 100% right. You do need to take time emotionally, you do need to look after yourself and you don’t have to do everything at once or juggle all the balls. But when it’s you – all that wisdom sounds like a cat poster. When it’s you, you believe that you should be the one who is capable of doing everything at once. Of keeping all those balls in the air. Because you are different. You are the one to do it. You can do what others can’t.

The truth is that they are right. You can’t. And that’s ok. Trying makes all the difference in the world even if sometimes you need to stop and get help or cry or have fresh air before getting back in the fight.

Still sounds like a cat poster though. And it always will.

At the end of the day, even though you feel like you might not be doing the best you can for your other kids, you know you are trying your best. In 30 years when they are phoning their sister to make Christmas plans or arranging a holiday for their families or just meeting for coffee and she’s still alive to do all that, then you’ve done your job right no matter what it took to get there.

Surgeries have generally been less dramatically emotional than the first time but the feelings are always there. Family and friends are massively supportive. During that pre-surgery night, two European friends stayed up talking to me on messenger until 2am (4am their time) to make sure I was ok then two hours later, they went to work. Throughout Covid, the family was bringing food packages from M&S, being there to talk to or providing the vital baby/dog sitting we needed. And while in no way would I ever negate the effect that family and friends have had, I’m sure they would be the first to agree that there’s a certain understanding and emotion that only the person in the room can know. If you’re that person in the room or have ever been that person in the room, you’ll know what I’m talking about.

The person in the room during treatment. The person in the room at 1am while the world is sleeping or that horrible ‘non-existent time’ of 5pm on a Saturday afternoon when the world is all either having fun or dinner or bored or watching final score and you’re in the hospital changing the bed for the fifth time in an hour because it’s got something all over it (again) or she’s shouting (again) because she can’t understand why she feels so rubbish and you’re shouting (again) because you’re frustrated that you can’t fix her and you don’t know which tap she wants water from. I remember one of the other parents once saying a similar thing: there’s a time in the room when it’s just you and her and you are the most helpless person in the world. You should be the one who is protecting her, who is keeping her safe; and yes, while you are doing that in an indirect way, the helplessness and isolation can be overwhelming. There are times when all you can do is let someone else work and trust them. For a person used to taking action both in personal life and job and a self-confessed control freak, that is not an easy feeling.

It’s at that time when the hospital staff also become family. For the last two years, Emmeline has grown up with these people: the nurses and doctors and consultants and anaesthetists and surgeons and play specialists and charity people and catering staff and baristas etc. Although she calls everyone a doctor. Some have been with us since the first day, they remember Edward being born and they’ve known Emmeline for over half her life. And she knows them as though they have always been part of her life, despite none of us having seen their full faces as Covid masks have been worn throughout. They are always available – checking how we are and whether we need anything, sitting with her so we can take a break after days in the room, trying to cheer her up with toys or dogs even though she’s resistant to most forms of entertainment – beyond their job descriptions. And above all they are literally saving her life and we will be forever in their debt.

It’s at that time when the hospital staff also become family. For the last two years, Emmeline has grown up with these people: the nurses and doctors and consultants and anaesthetists and surgeons and play specialists and charity people and catering staff and baristas etc. Although she calls everyone a doctor. Some have been with us since the first day, they remember Edward being born and they’ve known Emmeline for over half her life. And she knows them as though they have always been part of her life, despite none of us having seen their full faces as Covid masks have been worn throughout. They are always available – checking how we are and whether we need anything, sitting with her so we can take a break after days in the room, trying to cheer her up with toys or dogs even though she’s resistant to most forms of entertainment – beyond their job descriptions. And above all they are literally saving her life and we will be forever in their debt.

Postscript: While I’ve been writing this, Joe has just come into the room while she’s asleep to give her meds into her ng tube (the tube into her stomach through her nose). She hates it so we have to do it while she’s asleep in the hope that she won’t wake up and scream at him. It’s a delicate business which needs stealth, patience and cunning. He did it without stirring her and she’s still asleep. Nurse and safe-cracker in one. And he offered to get me a tea as well. Nothing sums up the support better than that.

The Noah’s Ark Charity recently launched an appeal to fund improved emotional support services for families like Emmeline’s.